Trade fog

The third type of fog is the fog surrounding trade talks. Despite Narendra Modi’s boasts about having a special and even a friendly relationship with Donald Trump, India is the only major country not to have struck a trade deal with the US. The blackmail tactics deployed by the US administration (with “reciprocal” US tariffs doubled from 25% to 50% to punish India for buying Russian oil) remain in force. Oil imports from Russia have fallen to their lowest level in three years, despite further discounts (of as much as $7 a barrel) for Indian refiners.

But purchases of Russian oil are not the only stumbling block in trade talks. The main obstacle – on which all free-trade agreements with India traditionally founder – remains the issue of opening up India’s agricultural sector.

The sector, which still supports the livelihood of over half the population, remains highly fragmented, consisting of family-owned subsistence farms. Indian farmers thus rightly fear that competition from US agri-food multinationals might wipe them out, especially considering that they are still negotiating floor price programmes with the government to secure a minimum level of income – a system that would be hard to reconcile with opening up the market.

Farming is an explosive issue: India’s farmers can mobilise on a massive scale. And, with the country’s most rural states making up Modi’s traditional base, the electoral implications are huge. Meanwhile, the US is aggressively pushing its own interests: outside of aerospace and cutting-edge chemicals, India’s trade surplus is mainly driven by exports of commodities – energy, oilseeds, cereals and cotton.

The US has imposed this agriculture and energy agenda in all its negotiations, forcing a number of markets to open up (notably in Malaysia, Thailand and the United Kingdom). Only South Korea has succeeded in holding its ground on rice and beef; however, it had a strong case (investment by South Korean companies, shipbuilding partnership, potential technology transfers in the semiconductor sector) – something India lacks.

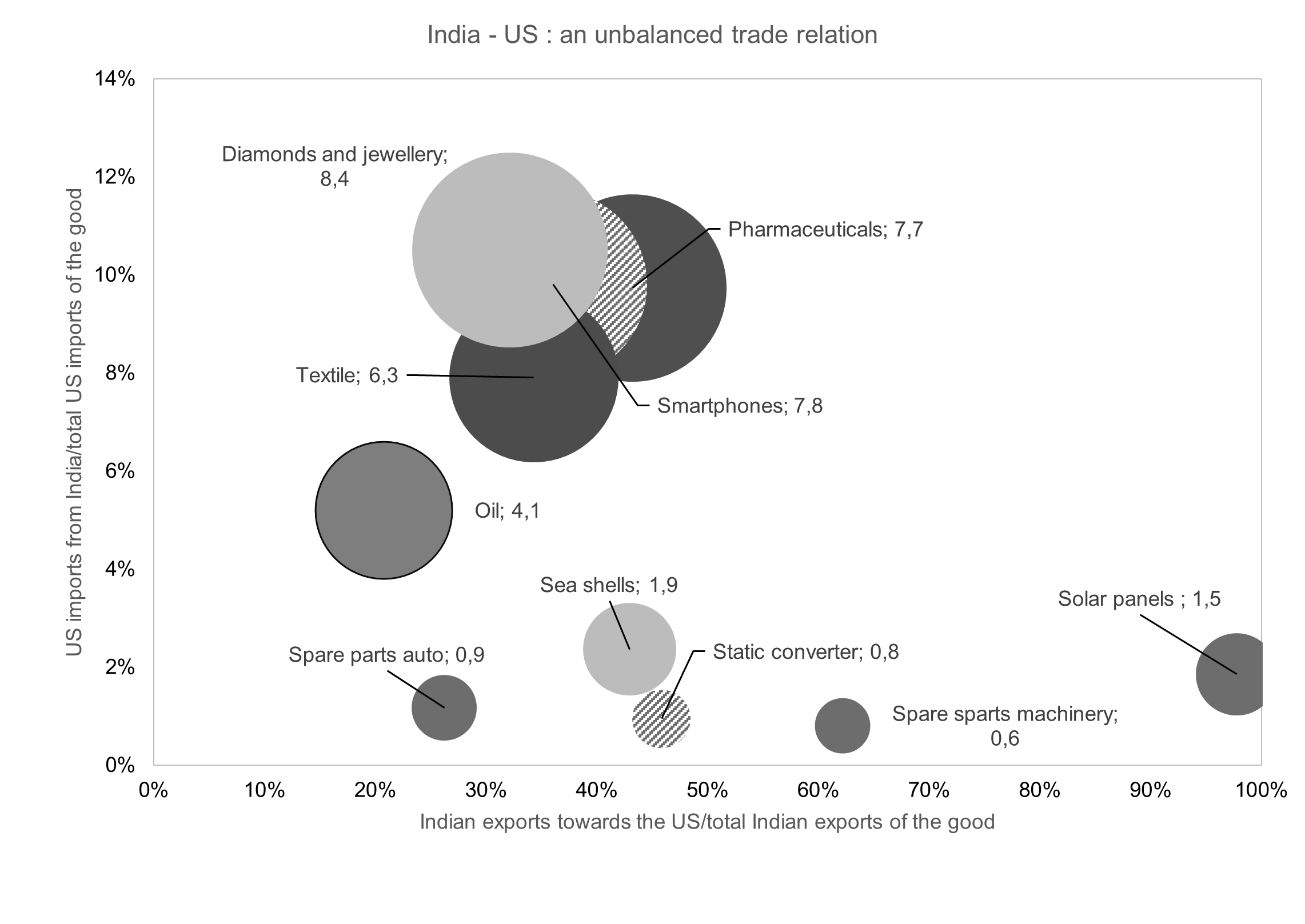

Trade relations between the two countries are thus very unequal. First and foremost there is the issue of the trade deficit – the Trump administration’s obsession – which has more than doubled since 2018 (from $21 billion to $44 billion). India is also one of the few countries to have a trade surplus in services with the US. Above all, there is a sharp asymmetry between India’s share of US imports (3% of total imports into the US) and the US share of Indian exports (22%).

Three sectors in India are particularly exposed to US demand: textiles, pharmaceuticals and mobile phones. US demand accounts for over a third of Indian exports in these sectors.

Generic drugs and mobile phones are exempt from import tariffs for the time being. US firms like Apple, which have opted to pull out of China to diversify their manufacturing base (mainly in India and Vietnam), have a lot of bargaining power with the US administration and are therefore unlikely to change their strategy and pull out of India in the short term.

In pharmaceuticals, where India plays a key role in the supply of many drugs, there are also few substitute markets offering the same levels of service as Indian manufacturers in terms of volumes and prices.

Conversely, in textiles, the risk of relocation to countries offering more favourable price terms is high. The sector provides over 45 million direct jobs. If the US market were to close to India, this would put many businesses in difficulty and have a big impact on the job market.

Lastly, while India runs a trade surplus with the US, this situation by no means reflects a general trend: in October, India’s total trade deficit in goods topped $300 billion. This makes its trade surplus with the US all the more valuable. After China, India is the country whose exports to the US have fallen furthest (with containerised exports from India to the US down 9.4% in September). However, unlike China, which is managing to get its products into the US through backdoor routes (mainly ASEAN countries and Mexico), India as yet has no alternative network.

Narendra Modi must therefore regain the upper hand in these tough negotiations, even if that means being prepared to shift the focus to areas other than trade, to secure a US compromise. Although India remains much more closed than its ASEAN competitors, its development path lies firmly along global trade routes.

Sources : TradeMap, Crédit Agricole S.A/ECO

These goods account for 50% of India’s total exports to the US. Hatched bubbles indicate that the vast majority of the goods in question are exempt from import tariffs.

“Crédit Agricole Group, sometimes called La banque verte due to its historical ties to farming, is a French international banking group and the world’s largest cooperative financial institution. It is France’s second-largest bank, after BNP Paribas, as well as the third largest in Europe and tenth largest in the world.”

Please visit the firm link to site