Synchrotron X-ray Fluorescence imaging works by scanning a sample in front of the intense X-ray beam generated by the synchrotron particle accelerator. The X-rays cause atoms in the sample to emit their own X-rays (X-ray fluorescence), which the scanning system detects. The properties of the fluoresced X-rays are specific to the chemical element they originated from. As such, this technique can be used to identify and map tiny differences in chemical elements locked inside fossils and in some cases, the chemical remnants of tissues no longer visible with visible light.

Dr Nick Edwards, a Staff Engineer for the X-ray Fluorescence Imaging beam lines at SSRL, performed the X-ray imaging experiments as part of a long-standing collaboration with The University of Manchester research team, with whom he worked with for his PhD studies.

He said: “Synchrotron X-ray Fluorescence imaging is a versatile technique with advantages over other types of scientific analysis that make it amenable to studying fossils. The experiments do not need special environmental conditions, and we can place relatively large objects in the instrument without the need to remove material from them. We can detect the extremely low levels of elements present in biological systems and correlate them to specific fossil tissues in a matter of hours. The results from these fossils are fascinating and further corroborate that the chemistry of extinct organisms can be preserved over huge geological time scales and be useful in interpreting the evolution of life.”

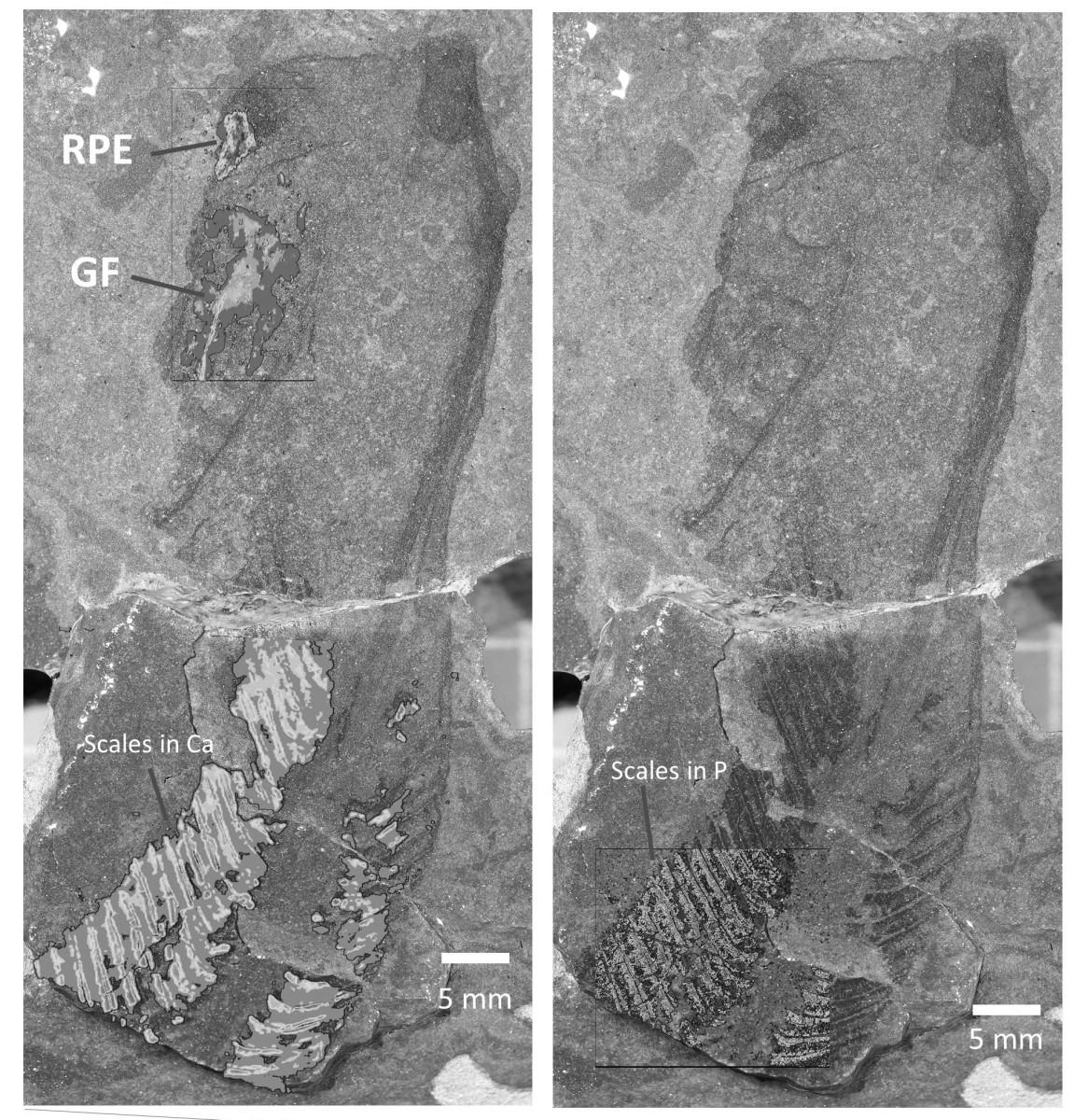

In this study, the team found traces of zinc and copper that revealed the structure of the retina and pigment layer in the ancient eyes. They also found calcium and phosphorus showing where early bone-like tissue was present.

The research has been praised internationally. Dr Pierre Gueriau of the University of Lausanne, who was not involved in the research, said: “This study not only rewrites some chapters of the evolutionary history of our early vertebrate ancestors, but also illustrates how advanced fossil imaging is not limited to CT scanning and encompasses a suite of analytical chemistry methods capable of revealing a new range of information, in some cases even considered lost to fossilisation. This is truly an exciting time to be a palaeontologist”.

Corresponding author Dr Robert Sansom, a palaeobiologist at The University of Manchester, added: “I love these fossil fish. They may have been dead for over 400 million years but they keep on surprising us with new hidden data about our deep origins.”

The team will now continue using this high-energy physics technology to tease out the chemical remnants of early life in other vertebrates, providing key insights into the evolution of animals such as birds, dinosaurs, mammals, and even microbial life.

This paper was published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B

Full title: Early vertebrate biomineralisation and eye structure determined by synchrotron X-ray analyses of Silurian jawless fish.

DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2025.2248

URL: https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2025.2248

“The University of Manchester is a public research university in Manchester, England. The main campus is south of Manchester City Centre on Oxford Road.”

Please visit the firm link to site