Nearly one in four adults in the U.S. lives with chronic pain(opens in new window).

Opioids like morphine help by reducing the brain’s perception of pain, but they come with risks and side effects researchers still don’t fully understand. Across neuroscience, biomedical engineering and artificial intelligence, esearchers from Carnegie Mellon University’s Neuroscience Institute(opens in new window) are exploring how pain is measured, understood and treated to support safer, more effective care.

Understanding pain behavior could unlock new treatments

For decades, the way researchers have measured pain in the lab hasn’t changed: They basically poke a subject with a blunt object or a pin and watch for a flinch, according to Eric Yttri(opens in new window), associate professor of biological sciences(opens in new window).

But that’s not how pain is experienced in the real world.

“It’s artificial,” Yttri said. “People with chronic back pain or nerve dysfunction aren’t spending their days getting poked with pins. They’re trying to live. They’re walking differently, rubbing a sore shoulder, avoiding the stairs, moving slower. That’s where the real story of pain is told. It’s not in a reflex, but in the movements of daily life.”

Yttri, an expert in behavior, was part of a team that studied better ways of treating pain. Led by Gregory Corder(opens in new window) at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, the team identified the specific part of the brain that makes pain feel miserable. Then, they developed a gene therapy that could eventually be used to stop that suffering without addictive painkillers like opioids. These game-changing results were recently published in the journal Nature(opens in new window).

Using the gene therapy to target a specific population of opioid-responsive neurons, the researchers were able to activate the brain’s natural pain-relief system without the risks associated with drugs. But to show the therapy truly worked, they needed more than a reflexive response. They needed to know whether it changed how subjects moved and behaved. That’s where Yttri’s team came in.

Yttri and Ph.D. student Alex Hsu provided a framework and set of tools that gave the researchers a shared, comprehensive language for describing pain-related movement. Their methods showed that while subjects could still feel touch and pressure, behaviors linked to distress or avoidance were significantly reduced.

The team used A-SOiD and B-SOiD, open-source AI algorithms developed in Yttri’s lab that autonomously categorize behavior. By analyzing movement in this way and creating a pain-specific behavioral library called LUPE (Light aUtomated Pain Evaluator), researchers could determine whether a treatment was truly easing pain, not just dulling sensation.

For people living with chronic pain, Yttri said, relief isn’t a simple on-off switch. There’s a third state where pain is present but no longer overwhelming. The algorithms helped researchers identify it.

Suppressing the neurons responsible for pain provided relief in the lab, Yttri said.

“We’re treating the emotional experience of pain,” he said. “You still feel the touch, the pressure, the reality of the injury. But the agony that keeps you from working or living — that’s what we’re aiming to erase.”

Bringing sickle cell disease pain into focus

Pain is a constant, complex companion that clinicians often struggle to understand and measure for people living with sickle cell disease. Traditional pain scales reduce this deeply personal experience to a single number that is often inaccurate.

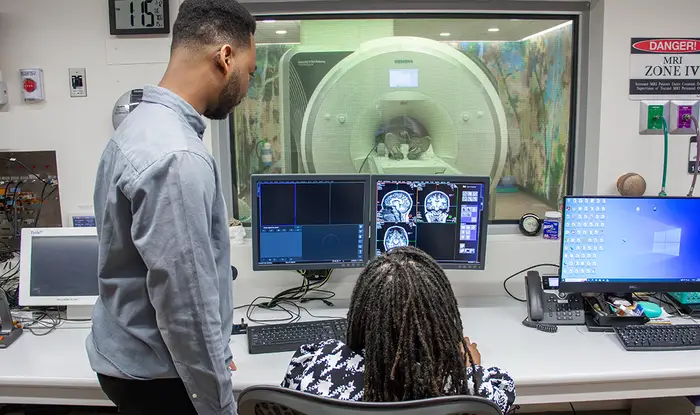

A study led by CMU’s Wood Neuro Research Group(opens in new window) takes a more human-centered approach, using advanced brain imaging and a digital visualization tool to illuminate how pain is processed in the brain, aiming to bridge the gap in pain interpretation between patients and clinicians.

“Traditional questionnaires only scratch the surface,” explained Joel Disu, first author of the Journal of Pain(opens in new window) paper and biomedical engineering(opens in new window) Ph.D. student. “They don’t capture the complexity or the internal experience of sickle cell pain. We wanted to see what happens in the brain when people describe their pain in a way that’s truer to how they actually feel it.”

The team explored how Painimation, a novel app developed by Emory University collaborator Dr. Charles Jonassaint, could help decode the neural signatures of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Instead of rating pain on a 1 to 10 scale, participants use animated visuals to describe what their pain feels like, for example throbbing, stabbing, cramping or shooting sensations.

Using ultrahigh-resolution MRI data, the researchers compared brain connectivity patterns between 27 patients with sickle cell disease and 30 healthy, pain-free participants. They focused on three key brain networks linked to pain perception: the default mode, salience and somatosensory networks. Their results showed that patients with sickle cell disease had significantly reduced connectivity across all three, particularly in regions involved in emotion, attention and sensory processing.

When the team linked these imaging findings to participants’ Painimation selections, a striking pattern emerged. Pain descriptors like cramping and stabbing correlated strongly with changes in the somatosensory network, the area responsible for processing physical sensations like touch and pressure. Moreover, patients who rated these sensations as more intense showed even greater disruption in those brain regions.

“This gives us a foundational step toward developing objective pain biomarkers,” Disu explained. “We can begin to see, in real time, how the quality and intensity of pain map onto the brain.”

Beyond its scientific novelty, the study addresses a critical gap in health care communication. Pain in sickle cell disease is frequently misunderstood, leading to mistrust between patients and providers. Many patients report managing their pain crises at home, because they fear being dismissed, being burdened by health care fees or being labeled as drug-seeking when they seek care.

“Our work helps visualize what has long been invisible or ignored,” noted Sossena Wood(opens in new window), assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Carnegie Mellon. “This research validates patients’ experiences with neuroscientific evidence. It shows that the pain they feel is real, measurable and rooted in brain function in vital pain receptors.”

The implications extend beyond research labs and translate to an accessible digital tool that can be assessed in the patient’s home. Painimation is already being adopted by several sickle cell communities across the country, helping clinicians better interpret pain experiences. Wood’s team hopes to build on these findings by exploring how tools like virtual reality and wearable sensors might one day help modulate pain perception or even reduce it through targeted brain stimulation.

Targeting pain at Its source

While some CMU researchers are focused on measuring and interpreting pain more accurately, others are working to stop chronic pain at the level of the nervous system itself. Andreas Pfenning(opens in new window), an associate professor of computational biology(opens in new window), is using artificial intelligence to design gene therapies that precisely target the cells responsible for chronic pain, without disrupting the body’s other essential sensations.

Much of Pfenning’s work centers on the spinal cord, a crowded and delicate hub where many different signals converge. In past work, he defined the cell types of the spinal cord(opens in new window) and linked them to chronic pain.

“In the spinal cord, you have some cells that transmit signals for chronic pain,” Pfenning explained, “but then there are other cells that are involved in normal touch or sensation, and you don’t want to mess with those.”

The challenge, he said, is precision. All cells in the body share the same DNA, but different cell types turn different genes on and off. Pfenning’s lab uses machine learning to decode this genomic language, learning what distinguishes a pain-transmitting neuron from a healthy one. With that information, his team can design genetic switches that activate only in the cells causing chronic pain.

“We can include a little signature designed by machine learning,” Pfenning said, “that says we’re only going to activate the gene in the cells that need it.”

In mouse studies done in collaboration with Rebecca Seal at the University of Pittsburgh, the approach has show promising results(opens in new window). The targeted gene therapy successfully blocked chronic pain signals while preserving normal touch, movement and other vital functions.

Though the work is still in its early stages, Pfenning sees chronic pain as a critical test case for safer, more targeted therapies. If successful, the approach could one day offer relief without the risks of opioids or the loss of sensation that often accompanies current treatments.

“Carnegie Mellon University is a private research university in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The institution was originally established in 1900 by Andrew Carnegie as the Carnegie Technical School. In 1912, it became the Carnegie Institute of Technology and began granting four-year degrees.”

Please visit the firm link to site