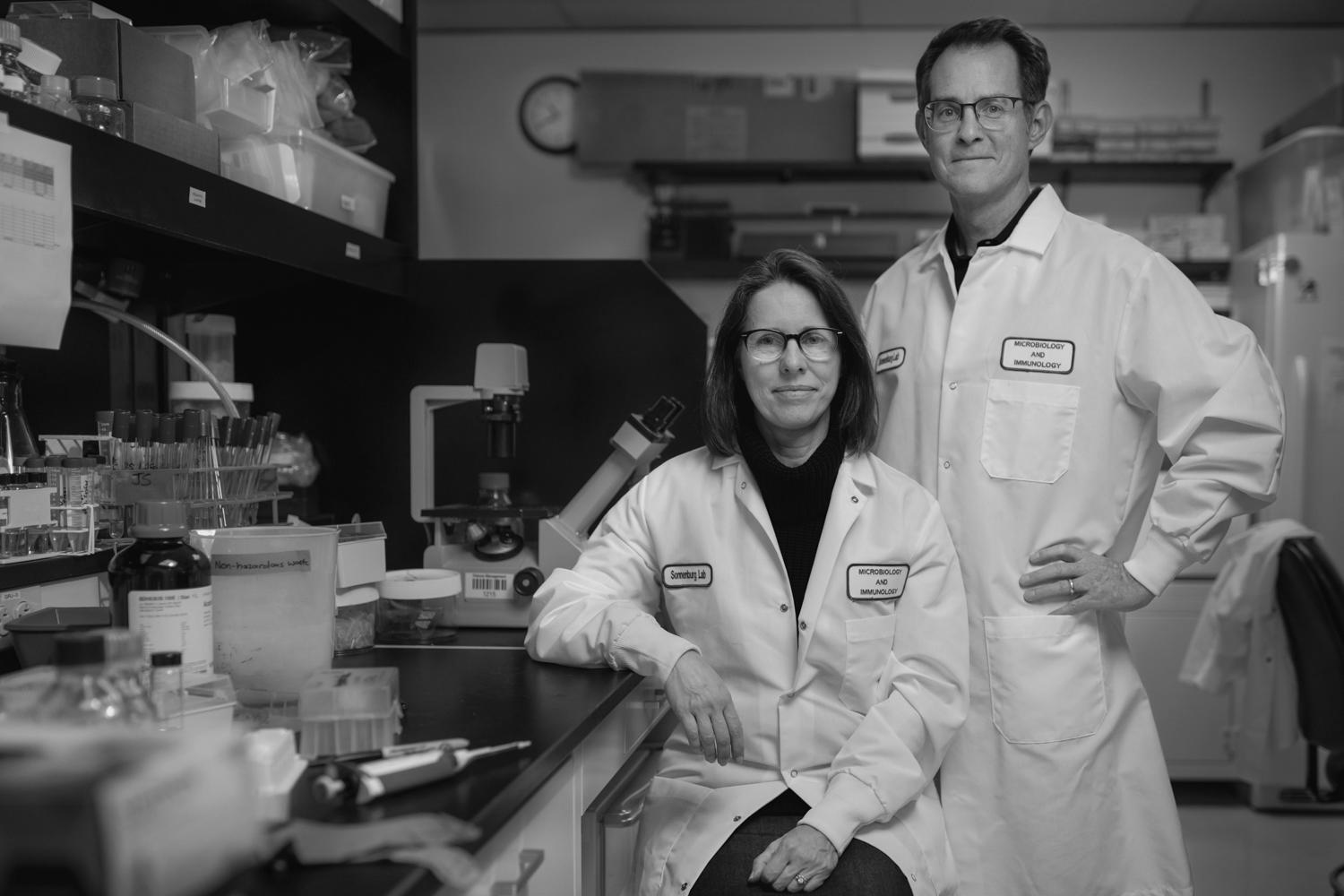

In the “Research Matters” series, we visit labs across campus to hear directly from Stanford scientists about what they’re working on, how it could advance human health and well-being, and why universities are critical players in the nation’s innovation ecosystem. The following are Justin and Erica Sonnenberg’s own words, edited and condensed for clarity. Their responses have been combined into a unified voice, with their approval.

When we first joined microbiome scientist Jeffrey Gordon’s lab at Washington University in 2003, we never anticipated how dramatically our careers – and lives – would change. We come from distinct scientific backgrounds – structural and molecular biology, and glycobiology – but we were both driven by curiosity about gut microbes and human health.

Twenty years ago, this connection was just beginning to be understood. Realizing that the microbiome was this untapped resource for influencing human health was very inspiring.

Initially, our collaboration was propelled by the encouragement of our mentor and we developed complementary aspects to our joint project. Our partnership quickly deepened as we had two children and could help each other manage work-life balance, setting the stage for establishing our lab at Stanford.

Advanced sequencing technologies developed from foundational NIH-funded projects like the Human Genome Project gave us the tools to really get an understanding of what’s happening genome-wise in the gut, and to ask and answer new questions. Imagine living on a coast your whole life, looking out at the ocean, and then all of a sudden, a boat is invented – it was kind of like that.

A large part of our research has to do with understanding how diet can promote a healthier microbiome and a healthy individual. One of our most dramatic discoveries was that dietary impacts on the microbiome have generational consequences. We found that mice fed a Western diet retained only a fraction of their original microbiome diversity after four generations. It was an amazing aha moment – not only can diet drive microbe extinctions, but the severity can compound over generations, where the parental generation can’t transmit microbes to their infants because of the deterioration of their own microbiome. This is what humans are doing right now.

These findings didn’t just influence our science; they profoundly shaped our personal lives. Like many in our field, we shifted our diets toward high fiber and fermented foods, aiming to nurture healthier microbiomes and reduce inflammation.

Industry has a short horizon – it needs to get to a profitable therapeutic result … [In academia] we don’t have that constraint, so we can actually address the structural problems – the root cause of many chronic diseases, inflammation.”

Two things really drive everything that we do in the lab. One is that the gut microbiome is malleable. We can change it, and that’s what makes it such a special part of our biology. When you eat different food, you don’t change the cells in your heart, but you can change the cells that are in your gut microbiome, fundamentally changing your biology. The second is that the gut microbiome is wired into everything – there’s no aspect of our biology that goes untouched by our gut microbiome in some direct or indirect way. It’s all connected.

The thing that keeps us in academia rather than industry is that industry has a short horizon – it needs to get to a profitable therapeutic result. These therapeutics are important in helping people, but amount to patching cracks in a foundation that has core structural issues. But, that’s the only financially viable model in industry. We don’t have that constraint, so we can actually address the structural problems – the root cause of many chronic diseases, inflammation. This long-term approach is required to reverse the rapid growth of these diseases.

Federal funding, especially NIH grants, has been central to our research. Early in our careers, this support was critical, allowing us to establish credibility and attract additional funding from foundations such as the Gates Foundation and the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub. Securing NIH funding is highly competitive, but this rigorous process strengthened our research and pushed us toward impactful science.

We are deeply concerned about the current funding climate. When we think about new professors or postdocs in our lab who are starting their own labs, we worry that continued funding challenges could easily result in losing a generation of talented scientists.

But the impact of our lab goes beyond the discoveries – it’s also all the people that we’ve trained and their contributions. It turns into this snowball effect, the two of us training dozens of scientists who will each then go on and train dozens of scientists. It accelerates the work and drives biomedical research forward, which will lead to people leading healthier and longer lives.

“Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies 8,180 acres, among the largest in the United States, and enrols over 17,000 students.”

Please visit the firm link to site