Following very high-level negotiations, notably involving US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and China’s Vice Premier with responsibility for the economy He Lifeng, said to be close to President Xi Jinping, the two countries said they were lowering their additional import tariffs for 90 days, from 145% to 30% for the US and from 125% to 10% for China. They also committed to continuing talks on their economic and trading relationship.

US-China tariff rates toward each other and rest of world (percent)

The US and China are heavily interdependent

Even before announcing that they were lowering their import tariffs, the two camps had granted exemptions on some products, highlighting the many sources of dependency that exist between their economies.

To understand these decisions, we need to look at the structure of US-China trade.

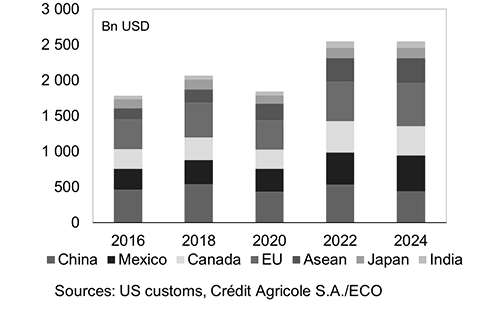

A few preliminary figures: in 2024, the United States imported Chinese goods worth $439 billion and exported goods to China worth $131 billion. China accounted for 13% of US imports and 7% of exports. Meanwhile, the US accounted for 15% of China’s exports and 6% of its total imports in 2024. Although US-China trade has fallen in both value and market share terms since 2018, the use of “backdoor” countries (particularly Mexico and Vietnam) suggests that, in reality, there has been little change in the overall level of interdependence between the two countries.

US imports

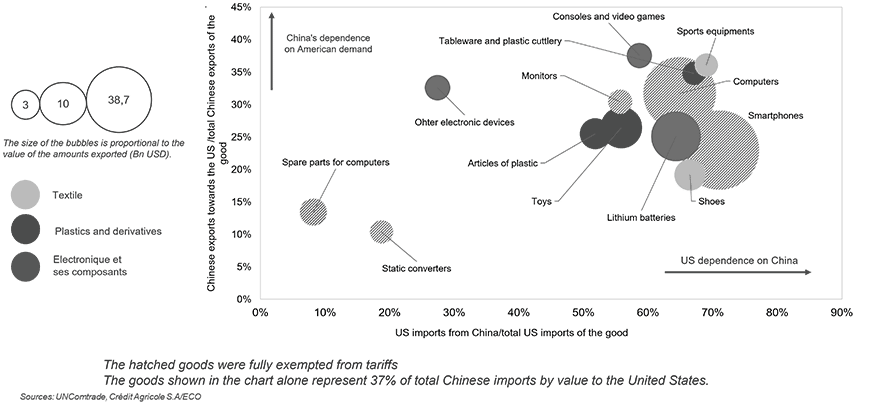

The US depends on China for mass market consumer goods (electronics, plastic items like toys, textiles and footwear, sporting goods and furniture) where production is not very capital-intensive but is relatively labour-intensive. It seems highly unlikely that these industries will be relocated to the US, where manufacturing costs would be much higher. When it comes to the value chain for electronic devices – notably computers and smartphones – where there are no alternative options in the short term, the Trump administration was quick to make concessions. Tariffs would have been passed straight on to end consumers, with an immediate effect on inflation. Even before official negotiations began, around 20% of total US imports from China were covered by exemptions.

One might, however, assume that the efforts made by major US companies in the sector – chief among them Apple – to decouple will continue, though it seems delusional to think that a network of subcontractors as dense as that offered by China might emerge in Vietnam or India (the two countries best placed to pick up production sites), and that’s without even considering quality in terms of logistics and transport and connectivity infrastructure available in China. The US had already undertaken to diversify its supply sources over the past few years, looking to South Korea and Taiwan for high value-added components and to the rest of Southeast Asia for less tech-intensive products.

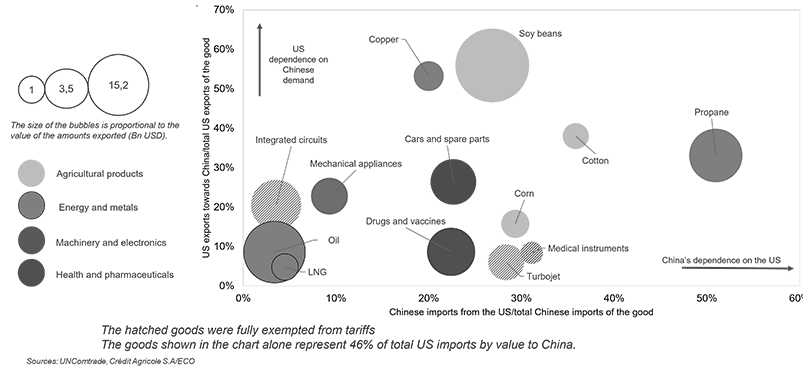

Meanwhile, Chinese exemptions covered sectors in which China is still somewhat behind the technology curve and is currently working to catch up: semiconductors, spare parts for aviation (particularly aircraft engines) and cutting-edge medical equipment. The rest of China’s imports from the US mostly consist of agricultural commodities (soybeans, maize and cotton) and energy commodities (oil, LNG and propane) where there are numerous diversification options that China has already begun to explore, notably with Brazil. This means the volume of imports covered by China’s exemptions was much smaller: around 10% of total imports from the US.

The final lesson is that the rest of the world is right to be worried: in the short term, Chinese exporters cannot afford to lose the volumes represented by US orders and will have to find other ways to move those volumes, either to the US via backdoor routes or to other countries. Conversely, it will take a lot of deals with the rest of the world for American farmers to be able to sell as much as they were able to in the Chinese market.

USA: exposure to Chinese products

China: exposure to US products

What should we take away from this first phase of negotiations?

In reality, the first lesson comes from the previous phase in the trade war: trade tariffs become rigid once they have been in place for a while, and it is difficult to restore them to their original levels. Despite the Phase One trade deal signed at the end of Trump’s first term following two years of steadily rising tariffs, the latter have never returned to their pre-2018 levels. Nor did the Biden administration question these levels. Although the level of these latest tariffs suggested that negotiations would take place quickly, there is nevertheless a risk that, even after negotiations, tariffs could remain persistently higher and would have to be absorbed by businesses or consumers in what would be a negative-sum game for both sides.

The second lesson is that, while the US has come out of this phase of negotiations with its image tarnished, it is perhaps China that has more to lose in the long term. In this poker game, the Trump administration is playing with a number of handicaps of which China is well aware. First, the markets, and particularly the bond markets, have already made known their profound opposition to trade tariffs, prompting the initial climb-down by the US administration. They might perhaps be willing to tolerate additional tariffs of 10% on the rest of the world and 30% on China, but not much more.

Second, American households have shown that they are much less resilient than their Chinese counterparts. The Democrats paid a heavy price for the increase in inflation between 2021 and 2023. Over the same period, Chinese households were facing an unprecedented real estate crisis that directly affected the value of their assets as well as huge job losses triggered by both the Covid crisis and regulatory changes in the new technologies sector. Because authoritarian regimes are not subject to the same electoral pressures, they are sometimes in less of a hurry to arrive at a deal. Xi Jinping, a child of the Cultural Revolution, often points out in his speeches that you sometimes have to endure difficult times in order to win battles.

Trump, meanwhile, values rapid deals and resounding wins. While maintaining additional tariffs of 30%, compared with 10% for China, allows him to save face, what remains of his credibility in negotiations – already seriously dented by the bizarre method used to calculate reciprocal tariffs – has been somewhat eroded.

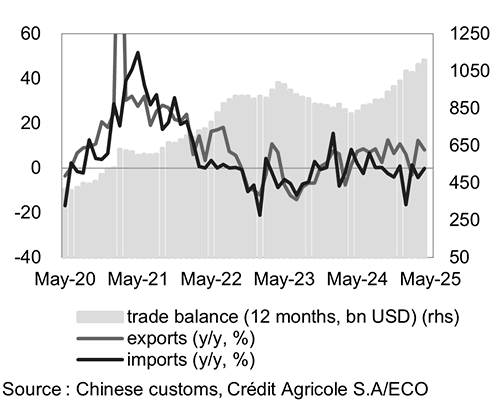

Lastly, China’s foreign trade figures for April defied all forecasts. Exports were up 8.1% year on year and the trade surplus climbed to a new high of $1.1 trillion. Chinese exporters have admitted to using backdoor routes to get their products into the US, but there is no denying that these numbers, published the day before negotiations were due to begin, put China in a strong position.

China: trade balance

In the medium term, though, China has more to lose from a genuine reconfiguration of value chains. Moreover, its priority was undoubtedly to secure the best deals in relative rather than absolute terms. China found itself in the extremely complicated position of being the only country to face additional import tariffs of 145%, while tariffs on the rest of the world had gone back down to 10%.

As we saw, China alone opted to up the stakes, while other countries immediately set about negotiating without hitting back or, in the case of the European Union, with targeted retaliatory measures. Isolated by punitive tariffs, China would have struggled to persuade the rest of the world to form a united front. During his travels in Malaysia, Vietnam and Cambodia, Xi Jinping did not manage to secure a firm commitment from those countries, despite their closeness, to condemn the US’s stance and rally to China’s side. The fact that tariffs on its products are now closer to those applied to other countries means it now has more cards to play.

Being the only country subject to 145% tariffs meant China was exposed to the risk of large-scale relocation of production sites. As we have seen since 2018, it is fanciful to imagine that the US can quickly and simply reduce the Chinese value-added content of its imports. The fact remains that, at a time when China faces fundamental questions about its growth model, with domestic demand still not able to take over from investment and foreign trade as the key driver of the economy, the prospect of losing production sites – and thus the associated jobs and economic activity – would have been hard to swallow.

In addition, China has little to offer in purely commercial negotiations with the US. The Phase One deal led neither to a rebalancing of trade nor to an increase in Chinese imports. On the contrary, China continues to pursue its threefold goal of diversifying critical imports (mainly commodities) and securing its independence in strategic areas while maintaining its export market share. These goals are far removed from – if not irreconcilable with – those of Trump, who is seeking both to expand markets for American businesses and to use import tariffs to fund his domestic policy of tax cuts.

The pause in the escalating trade war between the two camps is but one phase in the US-China clash. Each of the parties is well aware that it cannot remain as dependent on its strategic rival. For the US, this means finding new distributors in the rest of the world on equivalent price terms to those offered by China. For China, it means continuing the race to catch up in areas where it still lags behind the technology curve, with the aim of throwing off the shackles placed on it by the US in an attempt to slow it down.

In this clash, which for the time being is a lose-lose situation, the issues at stake in negotiations are many and varied. Trump has made no secret of his willingness to weaponise trade tariffs to exert pressure beyond the confines of trade. China is thus in his sights not only for its unfair trade practices but also for its role in the fentanyl crisis as an exporter of chemical components needed to make the drug. Rare earth mining and refining, integrated circuits, next-generation chips and microprocessors, market access, intellectual property protection, the yuan exchange rate: all these can and surely will be the subject of fresh talks. Re-escalating tensions cannot be ruled out, particularly if Trump feels that Chinese concessions are not commensurate with the “super deal” he hopes to strike. The negotiations are only just beginning.

“Crédit Agricole Group, sometimes called La banque verte due to its historical ties to farming, is a French international banking group and the world’s largest cooperative financial institution. It is France’s second-largest bank, after BNP Paribas, as well as the third largest in Europe and tenth largest in the world.”

Please visit the firm link to site