Unemployment: the price of stability?

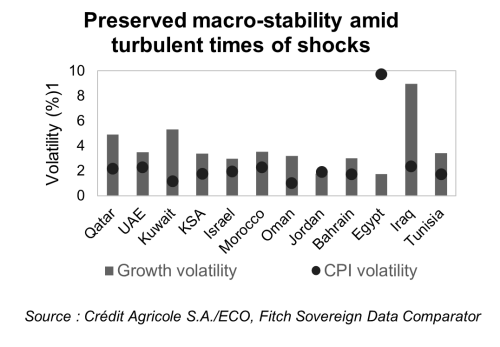

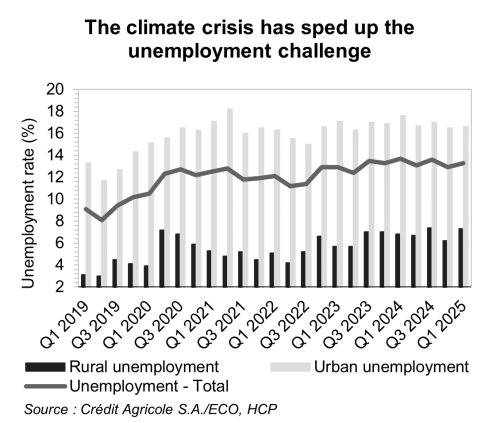

Morocco is steeped in a culture of stability which, looking beyond recent events and shocks, seems to be rooted in an older DNA probably related to the country’s political structure and attachment to monarchy. However, as the economy slows, it has become legitimate to wonder whether this attachment to stability – a mark of trust for investors – has in some ways gradually become an impediment to economic vitality. Having averaged 4.3% over the period 2004–2014, growth has subsequently flagged, averaging 2.5% over the period 2015–2024 – as though standing still were the price of stability1. The country seems to be approaching a crossroads where it is becoming difficult to maintain this compromise. In its latest report monitoring Morocco’s economic situation2, the World Bank notes that economic growth is failing to create enough jobs. According to the institution, “over the past decade, the working-age population has grown by more than 10 percent, while employment has increased by only 1.5 percent”. Consequently, unemployment reached a record high of 13.3% in 2024, compared with 13% the previous year.

Of course, the various shocks of the past few years have compounded the pressure. Water stress is a particularly significant factor, with the agricultural sector destroying jobs more quickly than other sectors can generate them in urban areas. In reality, though, this is merely exacerbating an underlying structural issue, in addition to which the agricultural sector is becoming less labour-intensive as its productivity improves, and the economy is transitioning towards services.

Injecting some fresh momentum?

Lately, though, there’s a sense that something is changing, that tectonic plates are shifting. The government’s reform plan – the New Development Model3 launched in 2021 – is based on a clear-eyed diagnosis highlighting institutional bottlenecks that need to be removed and reforms needed to untangle knots that are constraining growth. Ultimately, then, the World Bank’s report, which focuses on reforms to the business climate, is reassuring: overall, it is aligned with what the reform plan aims to achieve (improving the regulatory environment, incentivising the formalisation of the economy, removing barriers to competition, overcoming challenges to education, making public services more efficient, etc.). And the early results are beginning to make themselves felt. The economy is shifting firmly towards exports: over the period 2021–2024, exports of goods and services on average accounted for 41% of GDP, compared with 33.5% over the period 2016–2020. This is a sign that the country has awoken to its geo-economic strengths at a time when global production chains are being reconfigured. Of course, this means it is even more exposed to European growth, in particularly cyclical sectors (such as automotive, aerospace, electronic components and tourism) but also in strategic ones (Morocco’s high reserves of phosphate mean it plays a key role in global food security). However, none of this has so far moved the needle on unemployment. How, then, should this challenge be addressed in the short-to-medium term?

When economic interests and feminism align

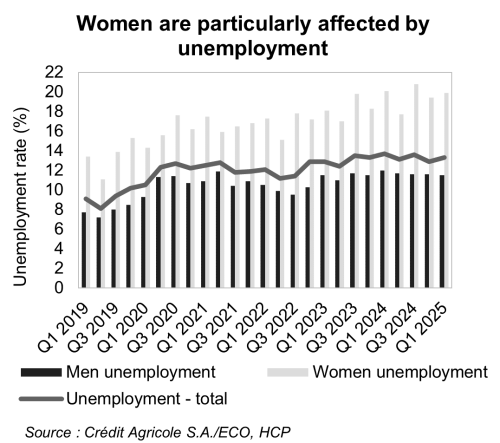

Taking a closer look, it is not only along the urban/rural axis that unemployment figures diverge. Female unemployment is increasingly acting as a brake on overall momentum.

Moreover, one trend highlighted by the World Bank is more surprising: while development indicators have improved in Morocco – in particular, the fertility rate is falling and women’s education is improving – women’s share of the labour market has plummeted from 30% in 1999 to 19% in 2024. This is one of the lowest levels in the world. It is therefore obvious that targeting the issue of women’s employment is one of the most effective keys to addressing the issues of Morocco’s stagnant growth and unemployment.

Here again, the economic transition and water stress are aggravating this structural challenge: agriculture is by far the sector that employs the most women. This means it is even harder for urban jobs to make up for the destruction of women’s jobs in agriculture: women in urban areas are hit harder not only by sectoral segregation and working conditions incompatible with parental responsibility but also by social norms around gender roles. This latter issue is particularly interesting: while the World Bank’s report includes the usual recommendations – for example increasing access to childcare solutions and adapting working hours and arrangements – it also offers a foretaste of a forthcoming study of the impact of gender social norms on women’s employment in Morocco.

Ladies, we love you

This forthcoming study used survey-based methods to gather empirical data quantifying the impact of social norms on structural constraints on women’s employment in Morocco. And, since the resulting figures are tangible and economic studies produced by such an institution are respected, we cannot resist giving you an early sneak peek of some salutary findings. First of all, ladies, we have allies: 81% of those surveyed said they were in favour of women working. Fair enough… but this falls to 62% when it comes to women working late, 61% for married women, 54% for women working in the absence of financial necessity and 21% for women working with a child under three years of age. Given that, what difference will childcare solutions make? But there is another even more striking finding. The initial figure of 81% (in favour of women working) reflects a shift in social norms: at the individual level, people are receptive to change. What is slower to shift, however, is perceptions of societal change: only 56% of respondents said they thought the community shared their opinion. In other words, the biggest obstacle to women working is fear of being judged by the community. Targeted information campaigns coupled with school-based interventions to change gender norms could prove essential in addressing Morocco’s growth and unemployment challenge.

“Crédit Agricole Group, sometimes called La banque verte due to its historical ties to farming, is a French international banking group and the world’s largest cooperative financial institution. It is France’s second-largest bank, after BNP Paribas, as well as the third largest in Europe and tenth largest in the world.”

Please visit the firm link to site