Federal finances are under pressure — and the pressure is increasing: The Federal Council recently had to admit that the procurement of the new F-35 fighter jets could cost up to 1,3 billion francs more than planned. At the same time, it further cut the planned savings package. As a result, deficits are looming again as early as 2028. There is little room for new spending.

It’s the worst possible time to be facing empty coffers. From a security policy perspective, Europe is facing a major turning point. NATO countries aim to increase their defense spending to 5% of GDP. Even neutral Switzerland is now expected to take a stronger role — even though, internationally, its situation isn’t as bad as is often suggested.

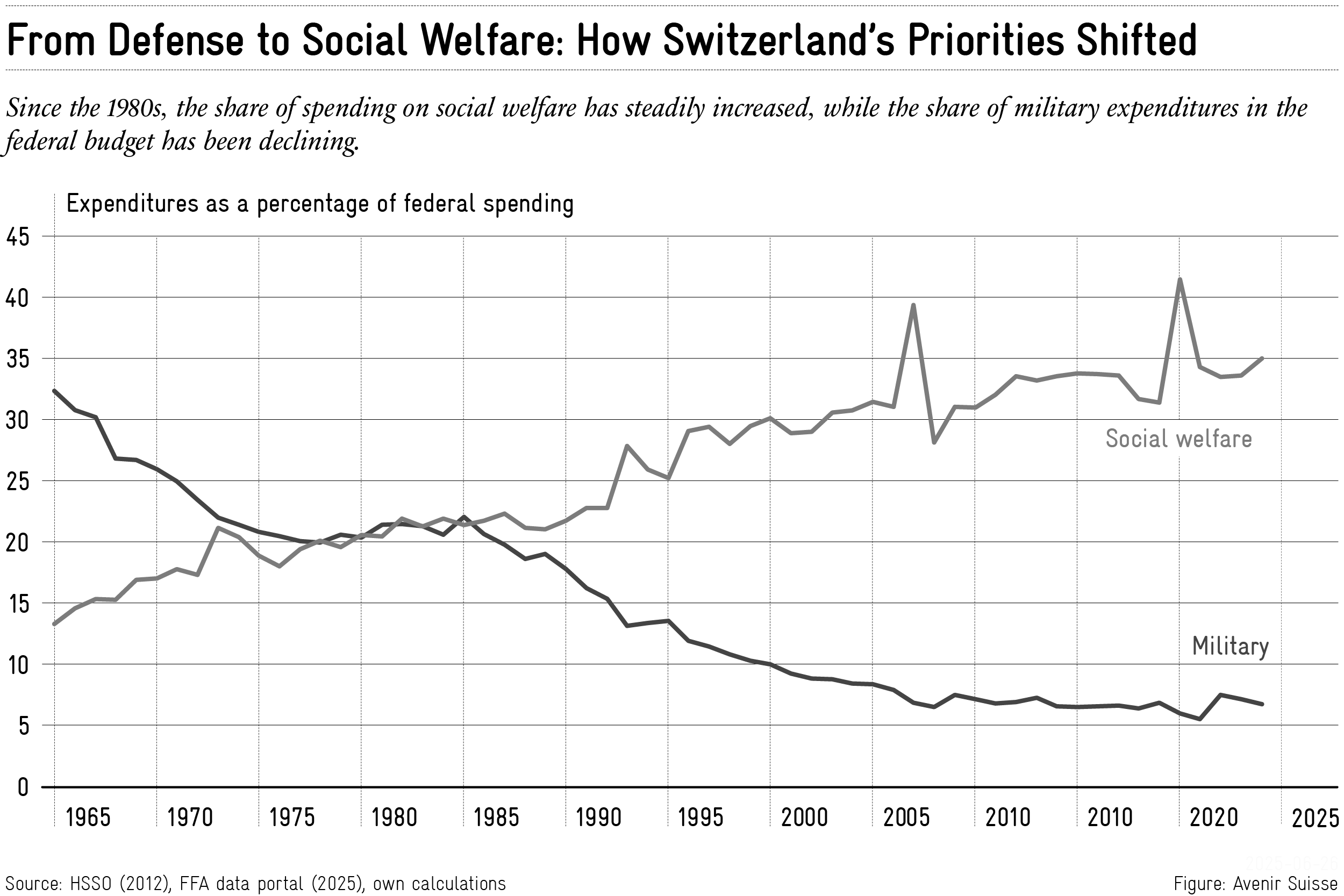

Parliament has already taken a first step: it intends to increase army spending to 1% of GDP by 2032. However, given the security situation, it is questionable whether this will be sufficient. A look at the long-term development of government expenditures shows, in any case, that additional funds for defense face significant challenges.

The Peace Dividend Flowed Into Social Security

The financial priorities of the federal budget have fundamentally changed over the decades. In 1965, nearly one-third of expenditures went to national defense. Today, that share is around 7%. At the same time, social spending has increased from 15% to over 35%. A reversal of priorities that has unfolded over six decades.

This development was no coincidence but a reflection of a period of relative stability: In the decades following the Cold War, the focus shifted. The threat environment appeared relaxed, and financial leeway increased. It was therefore logical to allocate part of the budget to social security. New social programs were created, and existing ones expanded. The aging population further contributed to this trend.

At the same time, the army was continuously reformed, streamlined, and organized more efficiently. Since 1990, personnel numbers have been gradually reduced—from up to 800,000 soldiers during the Cold War to about 140,000 today. This transformation made sense for a long time, but now it must be adjusted to new realities.

Structural Hurdles

The current imbalance is structural: saving in the social welfare system is politically difficult, while it is much easier in the military. The reason lies in the expenditure structure: two-thirds of federal spending is legally bound, with the majority allocated to social benefits. Anyone aiming to cut there often has to face a public referendum—with an uncertain outcome.

In contrast, the military budget falls under parliamentary control. Cuts can be made quickly—often with little political fallout. This is also why defense spending has declined for years. Although more funds are now flowing back into the military, the earlier reductions are now exacting their price: There’s no more fiscal room to maneuver, especially in a phase of growing threats.

High Opportunity Costs

How challenging the situation is becomes clear from a recent example: Swiss voters approved the 13th OASI pension, which costs over four billion francs annually. Even though the federal government only covers part of it, the scale is striking: the same money could buy 20 new F-35 jets every year—even at inflated prices.

Pointedly put: The 13th OASI pension costs as much as a complete renewal of the air force—every two years. This comparison is not an argument against social welfare systems but rather highlights the importance of conscious prioritization. Switzerland can afford both social and military security—but not both without limits.

“Avenir Suisse is an independent think tank that works for the future of Switzerland by developing evidence-based, liberal, free-market ideas.”

Please visit the firm link to site