Donald Trump equates trade deficits with theft from the American people. By that logic, he should be proud of the surpluses the US achieves in services trade. But in his view, only manufacturing really matters. In doing so, he overlooks the fact that the exchange of services (see box) is becoming increasingly important.

Trade economist Richard Baldwin even speaks of a new phase of globalization. The fragmentation of value chains is no longer something limited to industry: knowledge, ideas, and entire teams are increasingly less tied to one location thanks to digitalization. Consulting, research, or IT services are now delivered via data lines. The cloud is the new container, data the new raw material.

This development has also reached Switzerland. We have compiled the key facts on trade in services and highlight the policy levers that can be adjusted to improve the framework conditions.

1. What is the significance of trade in services for Switzerland?

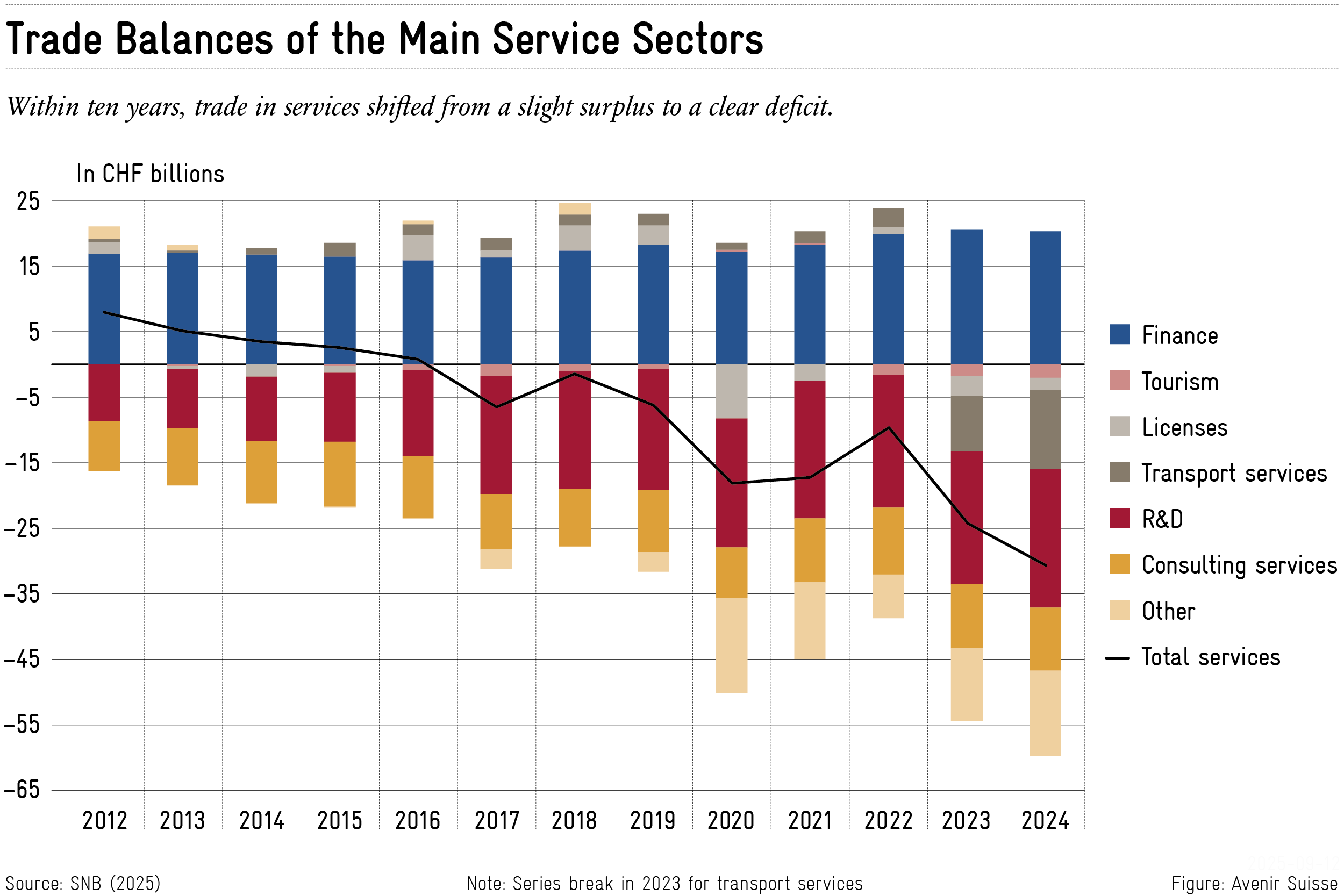

In 2024, Switzerland’s total trade in services—exports and imports combined—reached a value of CHF 347 billion, accounting for 41% of total foreign trade. Since 2015, it has grown by over 4% per year on average, outpacing trade in goods (3.5%). Imports of services increased particularly strongly, turning a small surplus in services trade into a deficit of just under CHF 31 billion.

2. Which sectors shape Switzerland’s trade in services?

On the export side, royalties and license fees lead (19%), for example when a US corporation markets a drug developed in Switzerland. They are followed by financial services (15%) and tourism (12%).

On the import side, royalties and license fees also dominate (17%), for example for software. They are followed by transport and R&D services, such as studies commissioned by Swiss companies in foreign labs. The strong increase in R&D orders is the main reason Switzerland has become a net importer of services in recent years.

3. Who are Switzerland’s key trading partners?

As it’s the case for trade in goods, the EU is also Switzerland’s most important partner in services trade. At the country level, the US leads, followed by Germany and the United Kingdom – for both imports and exports Switzerland imports more services from each of these countries than it exports to them. With the US, the services-trade deficit exceeds CHF 20 billion.

4. How many Swiss jobs depend on services trade?

Around 78% of all employed people in Switzerland work in the service sector. According to the OECD, 20% of all jobs are directly or indirectly linked to international services trade, which amounts to over one million positions.

This is particularly visible with multinational companies. In 2023, over 14,000 foreign firms in Switzerland’s tertiary sector employed 417,000 people. This represents a 28% increase over ten years, clearly outpacing job growth in the overall economy.

5. What hurdles exist in trade in services – and how open is Switzerland?

According to the OECD’s Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI), many countries have tightened regulations on international trade in services in recent years. This includes stricter licensing requirements for foreign providers or rules mandating that customer data be stored in the target country. These measures are driven by geopolitical tensions, national security interests, and the trend toward reshoring.

By international comparison, Switzerland performs well: rail freight, legal services, architecture, and distribution are very liberally regulated. By contrast, logistics, computer services, broadcasting, and courier services face relatively high barriers. Examples include the postal monopoly for letters under 50 grams and the ‘Lex Netflix,’ which came into force in 2024. The OECD also criticizes state participation in several sectors, as it can distort competition. In addition, there are restrictions on the free movement of self-employed service providers, and starting a business is comparatively cumbersome.

6. What should policymakers do?

If Switzerland wants to remain competitive in international trade in services, it must pursue three goals: secure market access, keep bureaucratic costs low, and make new technologies available. This is crucial because trade in services is a key export pillar for many Swiss companies.

What matters – just as in trade in goods – are the benefits for the economy and consumers, not whether the balance shows a surplus or deficit. High imports (and thus “deficits”) are not a sign of weakness—they can boost competition, quality, and variety, thereby strengthening Switzerland as a business location. The Swiss pharmaceutical industry is booming in part because it can rely on R&D in third countries.

It is important to strategically modernize existing trade agreements and conclude new ones, with a focus on digital services, free data flows, and mutual recognition of professional qualifications. A good example is the free trade agreement with India, which brings improvements in services trade.

Domestically, efforts should focus on three areas:

1. Lower trade barriers: In protected sectors such as logistics, digital services, as well as broadcasting and courier services, market access restrictions should be eased.

2. Reduce state participation: In sectors such as postal services or telecommunications, the government should scale back its ownership stakes and focus on core tasks. This reduces distortions of competition and strengthens Switzerland’s hand in international negotiations.

3. Screen new regulations for trade compatibility: Before adopting new laws, consistently assess whether they create unnecessary market entry barriers. For example, a requirement to store all customer data in Switzerland could exclude foreign providers and prevent Swiss companies from accessing international cloud services.

Trade in services is not a niche topic. While goods trade sparks loud debates over tariffs, services trade is quietly but steadily gaining importance. As a key to 21st-century-competitiveness, it definitely deserves much more attention.

Box: What counts as ‘trade in services’?

International trade is about more than watches, machinery, or chocolate. Services like tourism, financial advisory, transport, management consulting, licensing, or IT are also supplied across borders—often digitally and without crossing a customs checkpoint. The World Trade Organization (WTO) distinguishes between four modes of supply:

- Cross-border supply of services without a physical presence in the recipient country (e.g., distance learning).

- Consumption abroad by the service consumer (e.g., tourism).

- Establishment of a commercial presence abroad that provides services (e.g., a bank branch).

- Presence of natural persons (e.g., installation of a machine).

Measuring services statistically is tricky. For example, balance of payments statistics do not capture Mode 3 (services provided through a foreign branch). Yet the WTO estimates Mode 3 accounts for more than half of global services trade.

Classification is another major challenge: maintenance contracts that include both services and spare parts represent a mix of goods and services and therefore blur categories. Moreover, services are involved in the value chain of almost every product (e.g., product design), but are rarely recorded as such.