If Trumpism succeeds, the United States will not only adjust its foreign policy but could inaugurate a new post-Yalta international order – one bringing the West and Russia closer together. Trumpism affords a more compatible mechanism to resolve conflicts in the current bifurcated international system than the Western rules-based liberal international strategy, writes David Lane.

Donald Trump’s two presidencies embody elements of both a personal leadership style and the emergence of a broader political current, Trumpism. On the personal level, his politics have been shaped by instinctive, transactional behaviour, sometimes abrasive and mercurial but always bold and histrionic in style. Such personalized accounts, however, should not be conflated with a more systematic body of policies and practices. Trumpism indicates a profound change not only in the conduct of American domestic politics but also with regard to foreign alignments and commitments.

Trumpism

Perhaps surprisingly, the leaders of the major political parties in the United States set their own agendas, usually vague and undefined. Trumpism, by contrast, rests on a more discernible foundation. Its policy line can be traced to the Mandate for Leadership series, published by the Heritage Foundation from 1981 to 2023. Since the 1980s, such American think tanks have provided the intellectual and policy groundwork for what has become a critique of liberal globalised capitalism. A comprehensive range of policies (described in Project 2025, the latest edition in the series) have to be taken into account to understand the emergence of a new distinctive variant of American politics.

While not coherent as a political or economic doctrine, Trumpism fuses elements of neoliberalism and mercantilism; adopts a populist and anti-elitist political stance; cultivates loyalty to a charismatic leader; and affirms cultural and political values derived from American traditions. Rather than a new political economy paradigm, Trumpism heralds a return to a more traditional form of competitive liberal capitalism grounded in the sovereignty of the nation-state. It should be understood as a rejection of progressive, globalized liberalism. In its place, American nationalist capitalist values are constructed to legitimate government domestic and foreign policy. Interwoven with these positions is Trump’s combative, charismatic personality, which has fuelled personal quarrels with political leaders as well as with organisations at home and abroad.

Trumpism’s domestic economic policy is based on classical competitive liberal capitalism: private property, profit maximisation through market competition, and economic coordination through a combination of the stock exchange, financial institutions and government. What distinguishes Trumpism is the strengthening of Presidential authority over state finance, personnel and institutions and its unexpected shift in policy on international trade, investment and foreign alliances. Also, domestic issues raised by diversity, equity and inclusion policies which diverge from traditional values have to be rectified.

By consolidating greater Presidential executive control over key economic decisions and policy making, Trumpism shifts away from the neoliberal paradigm and moves toward a more state-directed and interventionist form of capitalism. For example, Trump has challenged the independence of the Federal Reserve by seeking to influence interest rates in ways that favour business growth and employment. He has introduced a major policy shift toward a protectionist international trade strategy: in 2024, on the eve of his second term, the average US tariff on imports stood at 2.5 percent. By April 2025, after steep levies on Chinese, EU, and Canadian goods, the average surged to 27 percent. Following trade adjustments later in the summer of 2025, the average settled at 18.6 percent. Although these are still below the levels of 1931–33, when tariffs reached 45 percent (and sometimes more). Such measures mark a dramatic break with US foreign trade policy and indicate a more assertive, positive developmental role for government.

Making America Great Again

This protectionist initiative is closely tied to the ‘Make America Great Again’ agenda. Its aim is to stimulate domestic manufacturing by making US products more competitive in the American market and by pressuring foreign producers and American owned corporations to relocate production to the United States. It also seeks to secure and enhance US technological advance. Trumpism in trade policy has revived state-led strategies advocated long ago by Maynard Keynes and others who criticized free trade as detrimental to national development. The objective is not only to restore manufacturing jobs (bolstering Trump’s working class electoral base) but, of wider international significance, also to reverse the United States’ relative decline in the international order.

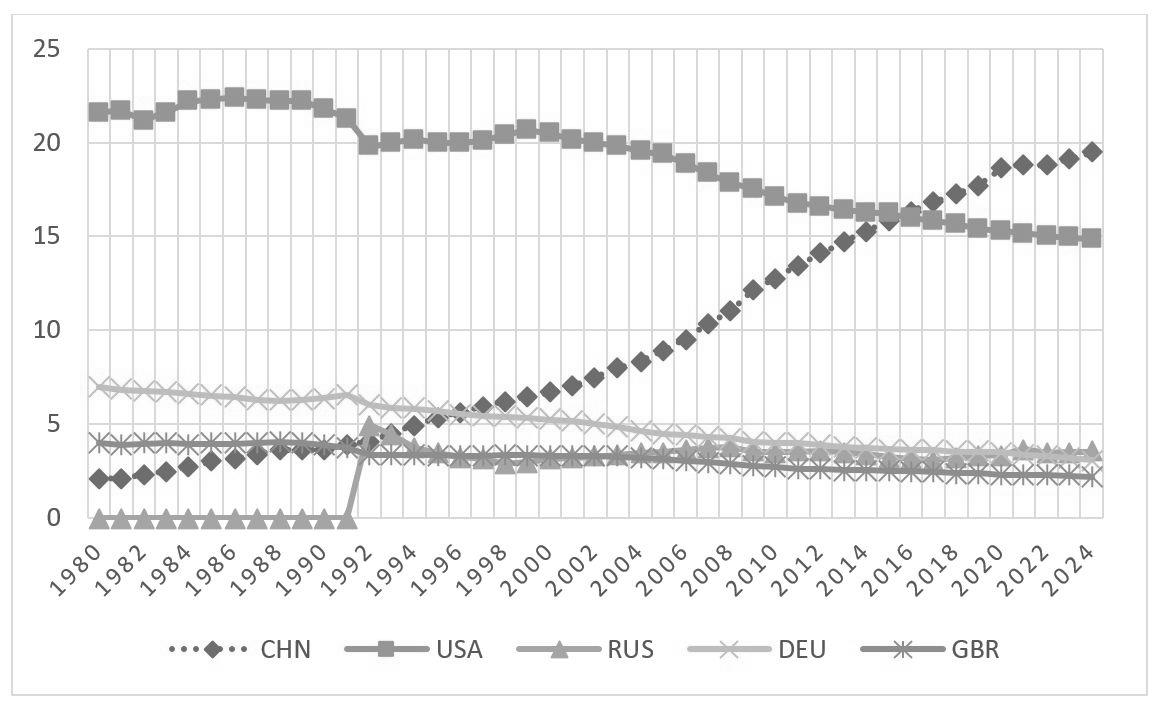

After the Second World War, the United States was the principal architect of the rules-based international order, projecting Western humanitarian political values and economic norms which underpinned the formation of NATO. It has sponsored military interventions in Korea, Vietnam, Cuba, Chile, Kosovo, Libya, Iraq, and Afghanistan and, under President Biden, NATO’s current proxy war in Ukraine. Unlike other established Western leaders, however, Trump and his circle acknowledge the emergence of a new international economic and political structure. The comparative decline of the United States and European powers, including Russia, is illustrated in Figure 1, which traces the proportion of world gross national product of major national economies between 1980 and 2024. In 2016, China surpassed the USA in gross national product; all the major European economies and the USA have suffered a continuous decline in their market share.

Figure 1. Proportion of World GDP (Purchasing Power Parity) (%), China, USA, Russia, Germany, UK, 1980-2024

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Data Base, April 2025.

Fault Lines in the World System

Running in parallel to the balance of global economic power lies a political fault line between two rival projects. On one side, stands liberal globalization, built on nation-state based corporate capitalism and coordinated by transnational economic bodies such as the IMF, the WTO and World Bank. On the other side, prevails state-directed capitalism with socialistic forms of control and collective ownership, most prominently championed by China, providing a model that directly contests Western hegemony.

Donald Trump has followed the liberal path. But he has broken the global rules-based liberal interventionist order in favour of a national capitalist political economy encased in sovereign nation-states. The USA has asserted its national authority by breaking agreements and production networks, brokered by transnational organisations, linking transnational corporations. For Trump and his allies, this is not merely a strategy for consolidating domestic support and conservative values, but an effort to offer the West itself an alternative form of capitalist internationalism. One which defines a viable route to making America, and the subaltern Western states, great again. Trumpism has not abandoned the pursuit of American hegemony but seeks to advance it through a more transactional strategy. Exerting political power takes place through economic sanctions and negotiated ‘deals’, not through direct military intervention – though this is not ruled out.

Trumpism does not rest on ideological commitments but on economic costs and benefits – a transactional calculation. ‘We do not seek war, we do not seek nation-building, we do not seek regime change ….’ His appraisal of the NATO/Ukraine – Russia war illustrates this logic: Western sanctions on Russia entail lost American business opportunities; and financial burdens on the US budget in support of the Ukrainian war effort do not benefit American tax payers. Even longstanding alliances such as NATO are subjected to transactional, cost-benefit scrutiny.

However, the military-industrial-security complex continues to function as a pillar in support of US strategy. This is not an aberration. It sustains American politicians and the corporations, communities, and workers dependent on defence contracts – thus, rendering the complex immune to political dismantling. Indeed, under Trump it has enjoyed increased state funding. While Trumpism questions alliances and promotes a deal-making foreign policy, the structural pillars of American hegemony remain. NATO continues to expand on American terms – designed to shift costs away from, and military contracts back to, the USA. Trumpism reveals both change and continuity: a rejection of liberal-internationalist interventionist ideology, but a reinforcement of the military and economic architecture that underpins the USA as the world’s hegemonic power.

What comes next?

Commentators who stress the divisive leadership style and personal authoritarianism of Trump miss the big picture. Trumpism is a non-ideological pragmatic transactional approach predicated on states’ interests. At the Helsinki 2018 Russia-United States Summit, President Trump invoked the memory of wartime cooperation between the United States and the USSR: an alliance again praised by President Putin (though not by Trump) at the Alaska Summit in August 2025. The Alaska meeting emphasised the positive advantages of trade and mutual economic benefits. Both Summits indicate that the Trump leadership envisages a rapprochement with Russia.

If Trumpism succeeds, the United States will not only adjust its foreign policy but could inaugurate a new post-Yalta international order – one bringing the West and Russia closer together (though on terms yet to be defined). Trumpism affords a more compatible mechanism to resolve conflicts in the current bifurcated international system than the Western rules-based liberal international strategy.

Whether this vision is reciprocated by Europe’s political elites, and whether it can survive resistance from entrenched opponents within the US deep state (and neo-conservative challenges in the Republican Party) is dependent on two decisive outcomes. First, can Trump’s trade and investment policies genuinely restore American industry, employment, and raise profits? Second, can his transactional foreign policy secure a lasting peace in Ukraine and resolve NATO’s relationship with Russia? Success on both fronts would vindicate Trumpism as an historical turning point, offering a national-capitalist alternative to liberal globalisation and a reconfiguration of the interventionist international order. Failure, by contrast, would discredit Trumpism domestically: Presidential power would be curbed; diversity, equity and inclusion policies would be reinstated and trade liberalisation would ease the terms for consumer imports. Internationally, an interventionist policy would be reinstated: geopolitical blocs would harden; the United States would renew, and perhaps deepen, the existing Cold War.

The Valdai Discussion Club was established in 2004. It is named after Lake Valdai, which is located close to Veliky Novgorod, where the Club’s first meeting took place.

Please visit the firm link to site