6 February 2026

Bulgaria adopted the euro on 1 January 2026. With this, Българската народна банка (the Bulgarian National Bank) became a full shareholder and the Bulgarian governor has taken a seat on the ECB’s Governing Council. This blog post explains what this means for the Eurosystem.

When a country adopts the euro, there is always extensive coverage of the expected implications on the sharing of monetary sovereignty for the country. This includes some concerns, but also expected benefits stemming from the adoption of the euro, like the fact that consumers can travel and companies can trade across Europe without having to exchange money. However, as with any enlargement of the euro area, Bulgaria’s entry also brings with it institutional changes for the Eurosystem. In this post, we focus on the implications for the ECB’s capital and other financial aspects, as well as for the voting rights in the Governing Council.

How Bulgaria’s accession affects the ECB’s capital

The ECB has its own capital, which enables it to operate and safeguard its financial independence from political influence – a principle, that of financial independence, explicitly recognised by the Court of Justice of the European Union in the Banka Slovenije judgment. The national central banks (NCBs) of the European Union (EU) are the sole subscribers to the ECB’s capital.

The ECB’s total subscribed capital of €10.8 billion is divided between all the EU NCBs. Each NCB’s share is calculated by the ECB using its capital key, which reflects the respective Member State’s share in the total population and gross domestic product of the EU.[1] Under the capital key, the Bulgarian National Bank’s (BNB) share of the total is 0.9783%, corresponding to €105.9 million.[2] This was the case even before the country adopted the euro on 1 January 2026.

What did change on that date, however, was the amount of BNB’s subscribed capital it had paid up to the ECB. This is because the NCBs of the non-euro area EU Member States are only required to pay 3.75% of their total share in the ECB’s subscribed capital as a contribution to the ECB’s operational costs.[3] This meant that before joining the Eurosystem, Bulgaria had already paid up slightly less than €4 million.

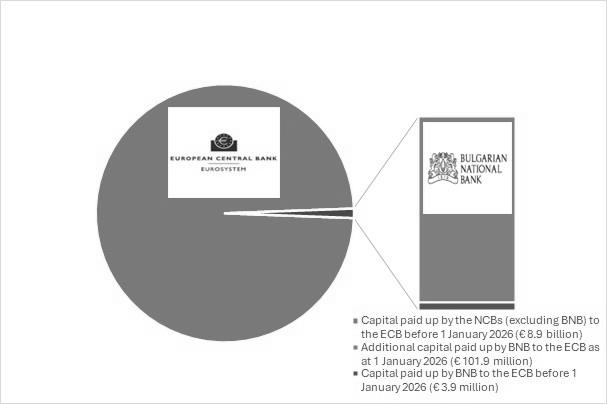

Chart 1

Composition of ECB paid-up capital after 1 January 2026 (€9 billion)

When it joined the Eurosystem, BNB had to pay the remaining 96.25% of its subscribed capital, amounting to €101.9 million.[4] As a result, Bulgaria’s entry into the Eurosystem increased the total amount of the ECB’s paid-up capital to €9 billion (Chart 1). This figure reflects the ECB’s total subscribed capital, excluding the amounts that the six non-euro area NCBs of the EU do not yet have to pay up.

BNB’s status before joining the Eurosystem meant it was not entitled to receive any share of the ECB’s distributable profits and was also not liable to fund any of its losses. Now, as an ECB shareholder, BNB is entitled to its full share in the ECB’s profits, in line with the capital key. It may also be required to contribute to the ECB’s losses if the Governing Council so decides, as set out in Article 33.2 of the European System of Central Banks and the European Central Bank (Statute of the ESCB).

Additionally, BNB now receives its share of income generated through monetary policy operations.

Besides paying up their share in the ECB’s capital, Eurosystem NCBs transfer foreign reserve assets and contribute to the ECB’s reserves and related provisions upon joining the Eurosystem.[5] The transfer of foreign reserve assets ensures that the ECB has sufficient liquidity to conduct potential foreign exchange operations. Contributions to the reserves, in turn, help cover part of the funds the ECB may use to address the potential materialisation of risks, especially those of a financial nature. In this context, BNB transferred foreign reserve assets to the ECB in proportion to its share in the subscribed capital.[6]

How decision-making has changed at the ECB

The ECB’s top decision-making body, the Governing Council, is responsible for setting the central bank’s monetary policy. Even before Bulgaria adopted the euro, BNB Governor attended meetings of the General Council, which among other things dealt with matters related to euro adoption. Now that Bulgaria is part of the euro area, Governor Dimitar Radev is a member of the Governing Council, which comprises the six Executive Board members alongside the now 21 governors of the euro area NCBs. The progressive enlargement of the euro area, and thus the growing number of members within the Governing Council, has made decision-making a complex logistical challenge.

Not all governors have voting rights for every decision. As the Economic and Monetary Union grew over time, it became important to keep decision-making processes manageable so that crucial decisions could be reached in a timely manner. To achieve this, the Statute of the ESCB, which sets out how the ECB functions, limits the number of voting Governing Council members to 21 once the number of NCB governors represented exceeds 18.[7]

When Lithuania became the 19th country to join the euro area in 2015, this threshold was reached and so a new system of rotating voting rights was implemented. Under this system, the six Executive Board members have a right to vote at all Governing Council meetings.[8] All other members of the Governing Council – the 21 governors of the euro area NCBs – share the remaining 15 votes on a randomised rotating basis, occasionally forgoing their voting rights.[9]

Some governors hold voting rights less often than others. To account for both the relative size and economic weight of their countries, as well as the importance of their financial centres, the governors are split into two groups. Voting rights within each group rotate every month on a randomised basis.

The first group consists of governors from the five largest euro area countries – currently Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands – who share four votes. This means that each of these governors forgoes their voting rights once every five months. In the second group, the inclusion of the Governor of BNB means that the remaining 11 votes are now shared by 16 governors, increasing the frequency with which each governor temporarily foregoes their right to vote. Currently four governors forego their right to vote each month.[10] Regardless of the voting rotation, all Governing Council members are entitled to attend all meetings, receive all documentation and exercise the right to speak.

The Governing Council reaches decisions collegially, based on consensus. In this context, the possibility to present arguments and participate in the discussion may be as important as the formal right to vote. However, some situations do require a formal vote. In these cases, the Governing Council decides by simple majority. This excludes decisions on certain types of shareholder matters, which include the ECB’s capital, the NCBs’ capital key for subscriptions to the ECB, the transfer of foreign reserve assets to the ECB, the allocation of monetary income generated by the NCBs in performing the monetary policy function and the allocation of the ECB’s profits and losses.

For these decisions, votes in the Governing Council are weighted according to each NCBs’ share in the paid-up capital of the ECB, while the six members of the Executive Board have a voting weight of zero.[11] With the Governor of BNB now in the Governing Council, BNB’s share is added to the total weighting of all the Eurosystem NCBs, slightly decreasing the relative voting weights of the other 20 NCBs in these shareholder decisions.

When a country joins the euro area, public attention usually focuses on the impact on the new member country. But changes also take place behind the scenes. The ECB’s paid-up capital – and therefore its ownership structure – is adjusted each time an EU Member State adopts the euro. When a NCB joins the Eurosystem, the voting system for ECB decisions is updated to accommodate the new member. Every time the euro area expands, the ECB evolves too.

The views expressed in each blog entry are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem. The views expressed in this entry also could not be interpreted as an official position of the BNB.

Check out The ECB Blog and subscribe for future posts.

For topics relating to banking supervision, why not have a look at The Supervision Blog?

“The European Central Bank is the prime component of the Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks as well as one of seven institutions of the European Union. It is one of the world’s most important central banks.”

Please visit the firm link to site